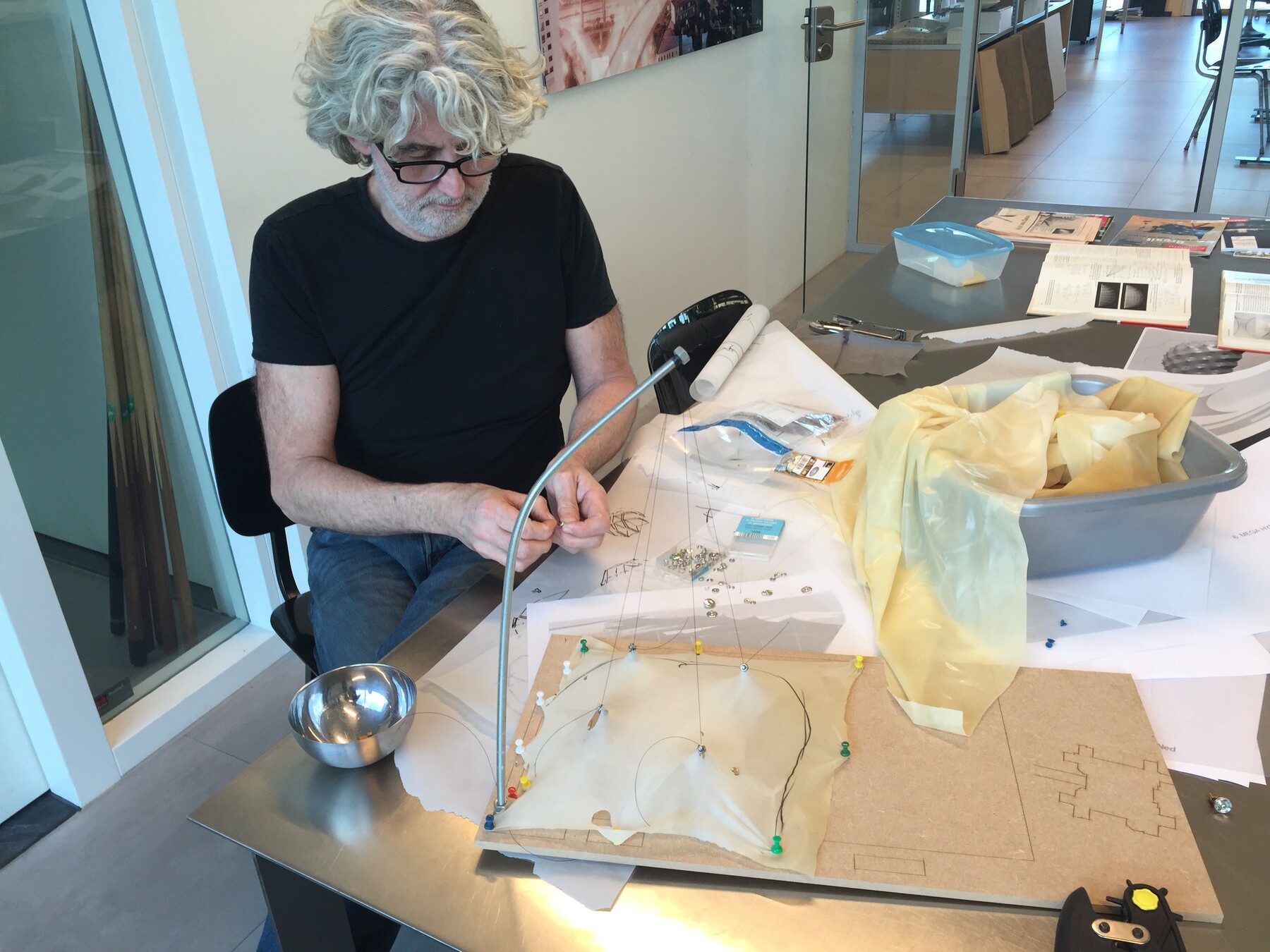

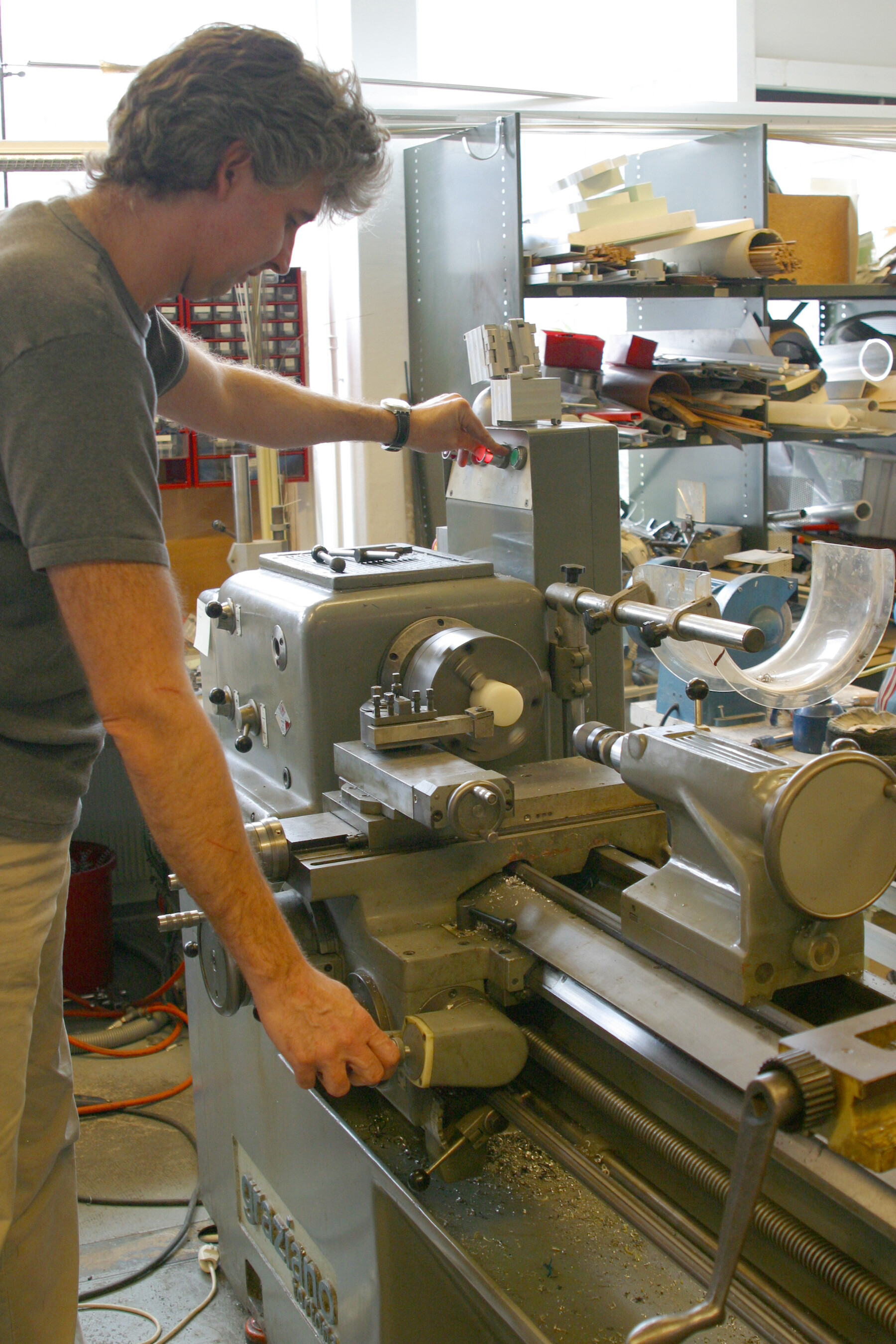

ZJA has grown to become a company employing more than fifty staff with more than fifteen nationalities. In 2000 and 2003 the board of directors was expanded to include Reinald Top and Rob Torsing respectively. Both had worked at ZJA for years, helping to strengthen it in an architectonic, business and organizational sense. In 2009 Moshé stood aside and retired. He died in 2019. Rein increasingly became the person who kept alive the connection between the design process, which concerned itself with functional and programmatic demands, and research into new structures, materials and design methods. Digital innovation, such as parametric modelling, and old-fashioned experimentation in the workshop with wood, concrete, steel, rope, laser cutters and 3D printers went hand in hand. Particularly impressive examples include the extended Waal bridge and the Diamond Exchange in Amsterdam.

Rein characterized himself as an über-rationalist who lived by intuition. His main source of inspiration seemed to be the self-organizing capacities of living nature, where without the involvement of any design, the most beautiful structures and efficient solutions emerge. To him design was ideally a kind of evolutionary process at maximum speed, of which chance, mathematics, rational demands and investigative dealings with wood, steel, rope, cloth and clay were part. In that process the interaction with others, and with other disciplines, was crucial. Rein was curious about shipbuilders, space-travel designs, artists and discoveries made by biologists. He applied that mentality to all the projects in which he was involved. Within ZJA he provided what he called ZJA’s humus layer: he arranged time and attention for play, pleasure, curiosity and experiment, which ultimately remain the source of all rational and useful design.